Numbers 19:1–11. The red heifer (Heb. parah adumah).

The Jewish sages teach that the commandment (mitzvah) of the red cow is “beyond human understanding.” Like the afikoman (the middle broken matzah that is “buried” and “resurrected,” which is a picture of the death, burial and resurrection of Yeshua) in the Passover (Pesach) Seder, the meaning of which to this day remains unclear to the Jewish scholars, the red cow is a ritual that makes sense only when Yeshua the Messiah is added to the picture.

While the symbolism of the red heifer was, to Jewish Torah scholars, admittedly incomprehensible to human reason, by the second temple era they began to speculate about its spiritual significance in their aggadic literature. Some felt that it was an atonement for the sin of the golden calf (The Encyclopedia of Jewish Religion, Massada – P.E.C. Press, 1965, p. 327; The ArtScroll Chumash, p. 839). Others viewed it as somehow relating to the azazel or scapegoat and the bullock sin offering of Yom Kippur, since all were sacrificed outside the camp of Israel (Lev 16:27).

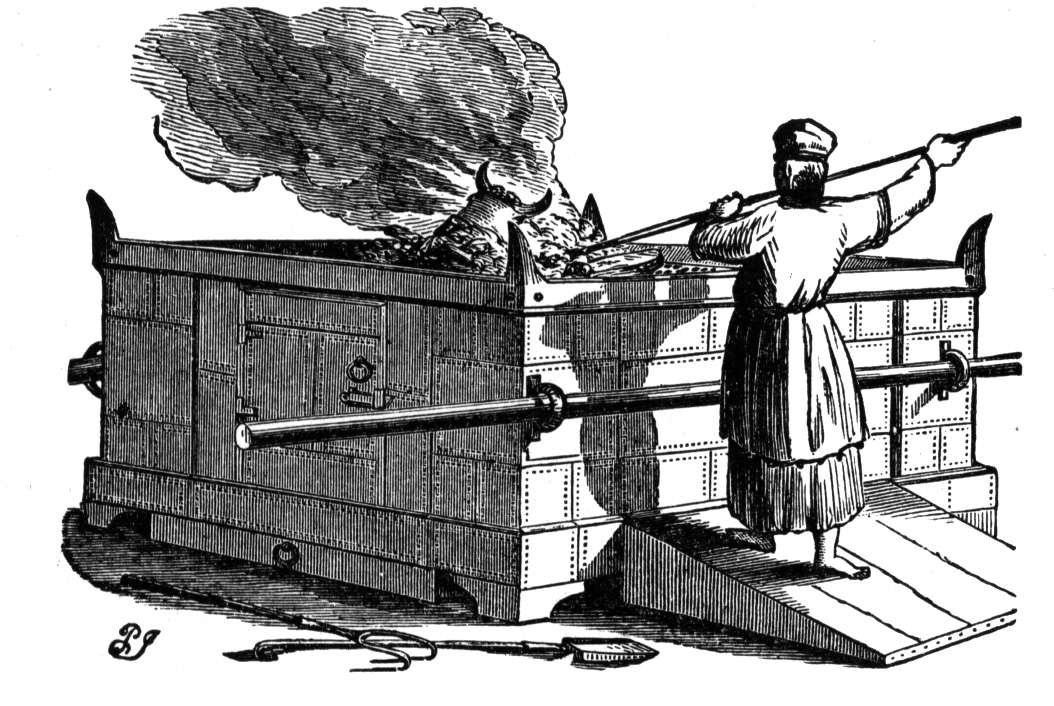

The sacrifice of the red heifer was for the purpose of purifying someone who had become ritually impure or polluted through contact with the dead, or for purifying metal war booty (Num 31:21ff). This sacrifice was to be made outside of the camp of Israel, and later occurred outside of the walls of the city of Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives, not far from the Temple. The concept of the camp signifies outside of or away from the divine presence or shekinah of YHVH meaning outside the tabernacle courtyard (The ArtScroll Chumash, p. 839).

The heifer was to be three to five years of age and totally red in color, blemish free and to have never born a burden and, according to Jewish tradition, to be without a single black or white hair on its body. The animal was slaughtered with the priest sprinkling its blood seven times toward the tabernacle’s entrance (later this occurred at the temple in Jerusalem). The entire carcass (hide, entrails and meat) was then burned on a wood pyre. Into the fire were tossed cedar wood, hyssop and a scarlet thread. The ashes were then divided into three portion: one part was kept in a secure place on the Mount of Olives (during the second temple period), one part was kept in the area immediately outside the wall of the temple courtyard, and one part was divided among the priests throughout the land of Israel to be used, as needed, in purifying the people (Mishnah Parah 3:11). The ashes to be used in the temple service were then mixed with fresh water (in Jerusalem, from the Pool of Siloam), and then called “waters of separation” (meyi nidah; nidah means “impurity, filthiness, menstruous, set apart, ceremonial impurity”), and were ritually sprinkled over something or someone that was impure. Numbers 19:9 states that the waters of sprinkling were for purification. The Hebrew word for purification is chatat, which according to some rabbinic interpreters is a reference to a sin offering (Ibid.). Others disagree arguing that the plain (pashat) meaning of the text does not speak of the red heifer atoning for sin (see Rashi’s commentary on this verse). This is an interesting debate, but regardless of what the Jewish sages think, the ritual of the red heifer shows striking parallels to Yeshua’s salvific work at the cross, as we discuss below.

The crucifixion implications of the red heifer were not missed by the Jewish-Christian scholar Alfred Edersheim. He links the Yom Kippur scapegoat, which was to remove the personal guilt of the Israelites (Lev 16), with the red heifer, which was to take away the defilement of death that stood between man and Elohim, with the “living bird,” dipped in “the water and the blood,” and then “let loose in the field” at the purification from leprosy (Lev 14:1–7), which symbolized the living death of personal sinfulness, were all, either wholly offered, or in their essentials completely outside the sanctuary. He then observes that the Old Testament sanctuary had no real provision for spiritual wants to which they symbolically pointed; their removal lay outside its sanctuary and beyond its symbols (The Temple and Its Ministry, pp. 280–281). This is why Yeshua had to be sacrificed outside of the temple area. Additionally, he had to be the sacrifice for sin outside of the temple area (Heb 13:12), which symbolized the shekinah or divine presence of YHVH. This speaks of the fact that the Father looked away, turned his back on and forsook Yeshua while he bore the sins of the world on his shoulders (Isa 53:4–6; Matt 27:46).

The writer of Hebrews understood the greater implications of the red heifer as it pointed to Yeshua when he wrote:

Which stood only in meats and drinks, and various washings, and carnal ordinances, imposed on them until the time of reformation. But Messiah being come an high priest of good things to come, by a greater and more perfect tabernacle, not made with hands, that is to say, not of this building; neither by the blood of goats and calves, but by his own blood he entered in once into the holy place, having obtained eternal redemption for us. For if the blood of bulls and of goats, and the ashes of an heifer sprinkling the unclean, sanctifies to the purifying of the flesh: how much more shall the blood of Messiah, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without spot to Elohim, purge your conscience from dead works to serve the living Elohim? And for this cause he is the mediator of the renewed covenant, that by means of death, for the redemption of the transgressions that were under the first covenant, they which are called might receive the promise of eternal inheritance. (Heb 9:11–15, emphasis added)

Eighteenth-century Christian commentator, Matthew Henry, asks why does the Torah make a corpse a defiling thing? He answers that it is because death is the wages of sin, which entered into the world by it, and reigns by the power of it. The law could not conquer death, nor abolish it, as the gospel does, by bringing life and immortality to light, and so introducing a better hope. As the ashes signified the merits of Messiah’s perfect sin-free life, so the running water signified the power and grace of the blessed Spirit, who is compared to rivers of living water; and it is by his work that the righteousness of Messiah is applied to us for our cleansing (Matthew Henry Concise Commentary on the Whole Bible, p. 137, Moody).

Continue reading