For those of you who are confused about when to celebrate the biblical Feast of Pentecost, this is a new article I have just written for you. I hope this clears up the confusion! — Natan

When is the Feast of Weeks (Heb. Chag Shavuot) or Pentecost? This has been a subject of debate among the Jews going back for two thousand years to the first century, and still is today among well meaning people who love Elohim and desire to follow his word. This is the question I will address in this study.

Since Shavuot is the only biblical holiday that involves counting days and weeks (hence its name, the Feast of Weeks), there are different opinions about when to start the count leading up to Shavuot. The Torah tells us to count from the Sabbath associated with the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

And you shall count for yourselves from the day after the Sabbath, from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering: seven Sabbaths shall be completed. Count fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath; then you shall offer a new grain offering to the LORD. (Lev 23:15–16, NKJV)

This sounds simple enough. Or is it?

The question and the subject of the debate is which Sabbath do you start counting from? The day after the weekly Sabbath occurring during the Feast of Unleavened Bread or the day after the high holy day Sabbath of the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which occurs on the fifteenth day of the first month of the biblical year?

In the first century in the time of Yeshua and the apostles, there were two main opinions among the leading Jews on when to start counting the weeks (called “the counting of the omer”) leading up to Shavuot. The religious sect of the Pharisees whose spiritual descendants are the modern rabbinic Jews started the counting of the omer from the day after first high holy day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which is a high holy day Sabbath (John 19:31). On the other hand, the Sadducees, the other main Jewish sects of the first century (along with the Boethusians, which was likely a sub-sect of the Sadducees; see A History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus Christ, second division, vol 2, p. 37, by Emil Schurer; Commentary on the NT from the Talmud and Hebraica, vol. 4, p. 23 [commentary on Acts 2:1], by John Lightfoot) counted the omer from the day after the weekly Sabbath that falls within the week of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Some modern Messianics follow the rabbinic method, while others follow the Sadducean method.

It is generally understood by historical scholars that the Jewish sect of the Pharisees interpreted the written Torah in light of Jewish oral tradition, while the Sadducees rejected oral tradition and adhered strictly to the written Torah (Schurer, pp. 37–38). According to Schurer,

In this rejection of the legal tradition of the Pharisees, the Sadducees represented the older standpoint. They stopped at the written law. For them, the whole subsequent development was without binding power” (ibid. p. 38). To the scribes and Pharisees, in contrast to the Sadducees, oral tradition took precedence over the Written Torah-law. It was intolerable to them that people should “interpret Scripture in opposition to tradition. The traditional interpretation and the traditional law are thus declared absolutely binding. And it is consequently but consistent when deviation from these is declared even more culpable than deviation from the Written Torah. It is more culpable to teach contrary to the precepts of the scribes, than contrary to the Torah itself [according to the B. Talmud, Sanhedrin ix.3]. (ibid. p. 12)

The first century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (37 BC to 100 BC) confirms this. He writes,

[T]he Pharisees have delivered to the people a great many observances by succession from their fathers, which are not written in the law of Moses; and for that reason it is that the Sadducees reject them, and say that we are to esteem those observances to be obligatory which are in the written word, but are not to observe what are derived from the tradition of our forefathers. (Ant. XIII.10.6)

Commenting on Josephus’ statement, Louis Finkelstein, a noted the twentieth century rabbinic scholar says,

This prolix statement simply confirms the talmudic record that the Sadducees rejected the Oral Law, which the Pharisees held equally authoritative with the Written Law. (The Pharisees, p. 261).

Yeshua himself castigated the scribes and Pharisees of his day for giving precedence to their Oral Law or the tradition of the elders over Elohim’s Written Torah in Mark 7:9, 13.

He said to them, “All too well you reject the [Torah] commandment of Elohim, that you may keep your tradition.…[Thus] making the word of Elohim of no effect through your tradition which you have handed down. And many such things you do.”

So we are still left with the following question: Which method of counting the omer toward Shavuot is correct? Do we follow the Written Torah or the Oral Tradition of the rabbinic Jews, which purports to follow the Written Torah but often doesn’t? That is the question I want to answer below.

To start, we need to first understand the meaning of some Hebrew words. Let’s look again at Leviticus 23:15–16.

And you shall count for yourselves from the day after the Sabbath [haShabbat], from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering: seven Sabbaths [Shabbatot] shall be completed. Count fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath [haShabbat]; then you shall offer a new grain offering to the LORD. (emphasis added, NKJV)

The word for weeks in this passage is the Hebrew word shabbatot. Does this word mean “weeks” as in “from the first day of the week (our Sunday) to the seventh day (our Saturday),” or does it mean “weeks of seven days” irrespective of which day in the week the count starts? I will attempt to answer this question later. Also it must be noted that the Torah here uses the phrase “seven complete Sabbaths” (Heb. shabbatot). This is important to note as we will see below.

The Hebrew word for Sabbath is shabbat. The plural form of this word is shabbatot, from which is our word Sabbaths derives, and is found later in the same verse (Lev 23:15). This verse says to count sabbaths, not weeks. Elsewhere the Bible clearly states that the sabbath is the seventh day of the week.

What do the Jewish rabbinical experts say about the meaning of Leviticus 23:15–16 and how to count the days toward Shavuot? After all, many Messianics view the Jews as the legal biblical experts that we are to follow in this regard.

To start with, the authoritative The ArtScroll Tanach Series Vayikra/Leviticus commentary is silent on the meaning of the word Hebrew word shabbatot in Exodos 23:15. The commentators offer no explanations as to why they chose to ignore the meaning of the word Shabbatot when counting the days toward Shavuot. They simply assume that the word shabbatot means “weeks” (shavuot) and not “sabbaths” without giving any explanation.

The nineteenth century orthodox rabbinic Torah scholar S. R. Hirsch in his commentary on this verse attempts to explain that the word shabbatot/sabbaths in Leviticus 23:15 when combined with the Hebrew word t’mimot (translated in English as complete or perfect) means “weeks of Sabbaths” or “weeks containing Sabbaths.” To justify this explanation, he cites, not Scripture, but a prior rabbinic Jewish tradition (i.e. The Babylon Talmud, Nedarim 60a). Thus, in his translation of the Torah, Hirsch says that the word shabbatot or sabbaths means “weeks of sabbaths.” Then in Leviticus 23:16, which reads, “the seventh Sabbath,” he translates the word shabbat as “sabbath-week,” even though this is never what the word shabbat means when used throughout the Hebrew Scriptures.

The Gutnick Edition Chumash takes a libertine approach and interestingly translates the Hebrew word shabbat in Leviticus 23:15–16 as “From the day following the (first) rest day (of Pesach)—the day you bring the Omer as a wave-offering—you should count yourselves seven weeks. (When you count them) they should be perfect. You should count until (but not including) fifty days, (i.e.) the day following the seventh week…” (emphasis added, parenthetical sentences are in the original). Here, bowing to rabbinic tradition and ignoring the meaning of the word shabbat, this translator translates shabbat/shabbatot respectively as “rest day,” “weeks,” and “week.” Other than that, this rabbinic commentator gives no explanation how he justifies translating the word shabbat as he does. He focuses on the command to count, but totally ignores discussing which day to begin counting from.

Similarly, The ArtScroll Stone Edition Chumash in its translation of Leviticus 23:15–16 also ignores the meaning of the word shabbat and changes the word shabbat to “rest day,” “weeks,” and “week” respectively. In its commentary section, this Chumash totally omits any discussion on the subject of counting from the sabbath, or which sabbath to count from. Similarly, Rashi, the pre-eminent medieval Torah scholar, in his commentary on this verse also presumes shabbat to mean “weeks” and cites earlier Jewish sources (i.e. Targum Onkelos) as his justification, but gives no Scripture to back up his claims.

The counting of the omer from the day after the high holy day Sabbath (and not the weekly Sabbath) was normative among the dominant Jews of the first century as attested to by Josephus who makes no mention of any alternative methods than that of the Pharisees for determining the beginning of the count of the omer (Ant. III.10.5).

These are the explanations, or lack thereof, that some of the top rabbinic experts over the past 2000 years have to tell us on this subject. This is not much to go on in order to make an informed decision about when to celebrate one of YHVH’s biblical feasts!

Contrary to what the above-quoted Jewish sages teach, The Theological Word Book of the Old Testament and Brown Drivers Briggs Lexicon, inform us that the word weeks [shavuot] is not one of the definitions of the word sabbaths [shabbatot], although BDB suggests that sabbaths or shabbatot could possibly mean “weeks of sabbaths.” Gesenius in his Hebrew lexicon suggests the same thing from the comparison of Leviticus 23:15 and Deuteronomy 16:9. The evidence supporting the meaning of “weeks of sabbaths” behind the Hebrew word shabbat is tenuous at best and should not, therefore, in all honesty, be used to build an argument on how to determine the time count leading to Shavuot.

Now let’s look at the Torah text itself, since the rabbinic scholars offer us little if any help in determining how to count the omer toward Shavuot or the Feast of Weeks.

If one were to view the day after the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread—assuming it doesn’t fall on a weekly Sabbath—as the first day of the count of the omer as the rabbinic Jews do, then how do you count seven sabbaths subsequently? For example, if the third day of the week (i.e. Wednesday) happens to be the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread and hence a sabbath (a high holy day Sabbath, but not a weekly Sabbath), then are all the remaining Wednesdays leading up to the Feast of Weeks also sabbaths, so that the command in Leviticus 23:15 to count seven sabbaths is fulfilled? The command to count seven Sabbaths only makes sense if one is counting seven actual weekly Sabbaths with the first weekly Sabbath being the seventh day of the counting of the omer and each subsequent Sabbath as the fourteenth day, the twenty-first day and so on until one arrives at the seventh Sabbath on the forty-ninth day of the counting of the omer.

At this point, someone may ask about Deuteronomy 16:9–10, which seems to lend credence to the rabbinic Jewish tradition that the Hebrew word shabbatot (sabbaths) means “weeks.”

You shall count seven weeks for yourself; begin to count the seven weeks [Heb. shavuot] from the time you begin to put the sickle to the grain. Then you shall keep the Feast of Weeks to the LORD your God with the tribute of a freewill offering from your hand, which you shall give as the LORD your God blesses you. (NKJV)

In this passage, we are instructed to count weeks, not sabbaths. Therefore, can we simply ignore the Leviticus 23 passage that clearly instructs us to begin our count toward Shavuot on the day after the weekly sabbath in favor of beginning the count on any day of the week, and to count seven weeks (i.e. Sunday to Saturday) instead of seven weeks of sabbaths as the rabbinic do? Not at all, for the instructions on counting to Shavuot is first mentioned in Leviticus 23:15–16 and therefore (in light of the biblical interpretive “law of first mentions”) forms the foundation or basis for all subsequent biblical discussion on the subject. Therefore, Deuteronomy 16:9 must be understood or interpreted in the light of the Leviticus 23 passage and not the other way around, even as the New Testament must be interpreted in the light of the Tanakh (Old Testament), since it came first and forms the basis for all subsequent divine revelation. Therefore, Deuteronomy 16:9 must be understood to mean “weeks of sabbaths” beginning from the first day of the week till the seventh day. Only in this way can Leviticus 23:16 be understood when it speaks of seven complete sabbaths being fulfilled upon arriving at Shavuot. This understanding reconciles these two passages in light of the biblical meaning and usage of the words shabbat (sabbath) and shavuot (weeks).

The closest analogous concept to weeks of sabbaths that we find in the Scriptures is the year-long land sabbath along with the seven sabbatical years leading up to the jubilee year. But in the biblical concept of seven land sabbaths, the pivotal point is still a definite sabbatical year when YHVH commanded the Israelites to let their land rest. The seven years is still tied to the year-long sabbath rest of the land, and the fiftieth jubilee year is calculated therefrom. The same is true from the day after the Sabbath, which is the first day of the week, when one starts counting toward Shavuot. After all, the Bible calls this holiday, the Feasts of Weeks. In Genesis chapter one, the Bible defines a week as being from the first day to the seventh day, which is the Sabbath (see also Exod 20:8–9). Unless otherwise stated, a week in the Bible means a week of seven days starting with the first day (Sunday) and ending on the seventh day or the Sabbath.

In conclusion, the verse that clinches the argument in my mind to help us to understand when to start the counting of the omer is Levitucus 23:16,

And you shall count for yourselves from the day after the Sabbath, from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering: seven Sabbaths [Heb. shabbatot] shall be completed.

Here, the Torah clearly states that the day before the Feast of Weeks is the weekly Sabbath. This is the plain meaning of the text and is what the Hebrew word shabbat means. By biblical definition based on how this word is used, the word shabbat can only refer to three things: the weekly shabbat, the Day of Atonement or the land sabbath. In the context of Leviticus 23:16, shabbat can only refer to the weekly Sabbath. Only rarely (about once in seven years) when using the rabbinical method to count the omer to Shavuot does the seventh Sabbath fall on the weekly sabbath. When one begins the counting of the omer from the day after the weekly Sabbath during the Feast of Unleavened Bread, Shavuot always follows the weekly Sabbath. With the rabbinic counting method, their Shavuot usually falls on the morrow or day after the seventh Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and so on, and only once in seven years on the morrow or day after the Sabbath. Therefore, their method of counting doesn’t meet the criteria as outlined in Leviticus 23:16, and which states that the day before Shavuout must be a weekly Sabbath.

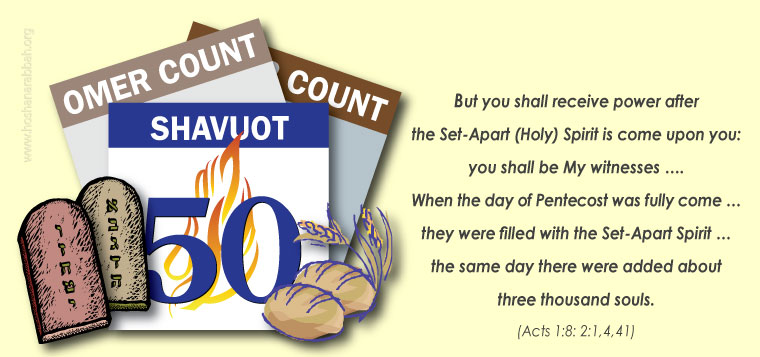

Perhaps this explanation gives us a fuller understanding into the phrase found in the Torah, “seven Sabbaths [Shabbatot] shall be completed” (Lev 23:15), or to a similar phrase found in the Book of Acts, “When the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place” (Acts 2:1). What is a complete [weeks of ] Sabbaths? It seems to indicate a complete or whole week from the first day (Sunday) to the seventh day (Saturday/Sabbath) with not a day lacking. Seven of these must be fully completed to arrive at Pentecost. It is interesting to note that Acts states, “When the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place” (Acts 2:1).

Moreover, it seems that the counting of the omer, which is seven seven-day weeks for a total of 49 days (7 times 7) symbolically points to “a complete completeness” representing the spiritual growth and development of the saint as they mature into perfect unity with YHVH and with their fellow saint, so that they will be spiritually prepared to receive the inner Torah of the heart, the gifts of the Spirit, and come to a place of being together and in one accord within the body of Yeshua to be able then to do the great commission and to reap the wheat harvest of lost sheep of Israel necessary to establish YHVH’s kingdom as per Acts 1:6–8 as pictured by the Feast of Pentecost.

What’s more, the weekly seventh day Sabbath is a prophetic spiritual picture of the one-thousand year-long millennial reign of King Yeshua’s on this earth, while a first day (Sunday) Shavuot is a picture of seven days plus one (or the eighth day) that prophetically points to “the spiritual upper room” of the New Jerusalem as outlined in Revelation chapters 21 and 22, when the glorified saints will dwell together and in one accord and in one place with YHVH Yeshua forever.

Perhaps the most important argument in favor of counting the omer from the day after weekly Sabbath during the Feast of Unleavened Bread is that this perfectly points to the resurrection and ascension of Yeshua the Messiah. The Gospel account is clear that he rose from the grave at the end of the weekly Sabbath and at the beginning of the first day of the week, and that he most likely ascended to heaven on the first day of the week when the wave sheaf offering was being made on Wave Sheaf Day (Lev 23:9–14). Yeshua’s resurrection and ascension during this time frame perfectly fulfills all the prophetic types and shadows in the Torah that pointed forward to him. (For a full explanation of this, please see my article, “The Resurrection of Yeshua from a Hebrew Perspective Prophesied in the Hebrew Scriptures,” at https://www.hoshanarabbah.org/pdfs/firstfruits.pdf.)

It is my contention that to count the 49 days of the omer leading to the Feast of Weeks in the rabbinic Jewish way takes away from the glorious spiritual, prophetic picture of Yeshua and his spiritual bride to be.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave