The secret [intimate, confidential counsel, advice or speech] of YHVH is with them that fear him. (Ps 25:14)

Introduction to the Bible

The Number of the Books of the Bible

The first point in determining the symmetry of the Scriptures is to realize that originally the Tanakh (Old Testament) was subdivided into 22 books, not the 39 in our present Bible. There was no difference in the content between then and now but only in how the books were categorized. The Book of Jubilees, a Jewish pseudepigraphic work dating to the second century b.c., attests to the fact (Jubilees 2:23) of there originally being 22 books in the Tanakh, as does Josephus in his Contra Apion (Book 1.8), and as do many early Church fathers and other early Christian scholars (In Restoring the Original Bible, Ernest L. Martin references 22 such early Christian writers, including Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History, 4.26.14, Martin, pp. 58–60).

It is believed that Ezra the scribe originally arranged the books of the Old Testament in this manner. Thus, books such as Samuel, Kings and Chronicles were combined into one book each and the 12 Minor Prophets were combined into one book as well. We will discuss the significance of the number 22 in the Scriptures below, but for now, how did the Tanakh get expanded from 22 to 39 books? According to Martin, the Jewish translators of the Greek version of the Tanakh (the Septuagint or LXX) in the second and third century b.c. subdivided the books of the Tanakh into the pattern we have today. There were, however, no Hebrew manuscripts that followed the Greek version (Martin, p. 65). Sometime in the last part of the first century or beginning of the second century a.d., Jewish authorities decided to re-divide the Tanakh into 24 books rather than to maintain the 22 (Martin, pp. 67–68). Eventually the Jews adopted the Christian numbering system of the books of the Tanakh found in the modern Protestant Christian Bible.

“There may well have been political and religious reasons why the Jewish authorities made the change when they did. When the New Testament books were being accepted as divine literature by great numbers of people within the Roman world, the non-believing Jews could see that the 27 New Testament books added to the original 22 of the Old Testament reached the significant number 49 [7 x 7]. This was a powerful indication that the world now had the complete revelation from God with the inclusion of those New Testament (or the Testimony of Yeshua) books. Since Jewish officials were powerless to do anything with the New Testament, the only recourse they saw possible was to alter the traditional numbering” (Martin, p. 68).

The Significance of the Number 22 in Hebrew Thought

Next Martin draws our attention to the ancient Jewish Book of Jubilees which mentions the significance of the number 22 in Hebraic thought. Annotated to the restored text of Jubilees 2:23 is the remark that Elohim made 22 things on the six days of creation with man being the twenty-second created thing—the crowning achievement of YHVH’s creative activities. These 22 events paralleled the 22 generations from Adam to Jacob (i.e., the Israelite nation being the crowning achievement of YHVH’s work among the nations of the world with Israel being the vehicle through which redemption would occur), the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, and the 22 books of the Holy Scriptures (Martin, p. 57).

The 22 numbering is most interesting and fits in well with the literary and symbolic meaning of “completion” as understood by early Jews. The Book of Jubilees put forth that this number represented the “final” and “complete” creation of Elohim. Adam was the last creation of Elohim (being the 22nd). Jacob, whose name was changed to Israel, was the 22nd generation from Adam; and Jacob was acknowledged as the father of the spiritual nation of Elohim. In addition to this, it is important to note that the Hebrew language became the means by which Elohim communicated his divine will to mankind. It had an alphabet of 22 letters. And, finally, when Elohim wished to give his complete Old Testament revelation to humanity, that divine canon was presented in 22 authorized books. The medieval Jewish scholar Sixtus Senensis explained the significance of this matter (Martin, pp. 57–58).

As with the Hebrew there are twenty-two letters, in which all that can be said and written is comprehended, so there are twenty-two books in which are contained all that can be known and uttered of divine things.

Yeshua the Messiah In Every Book of the Bible

The Bible has a dominant theme, and every Christian has a sense of this. The Old Testament or Tanakh points forward to Yeshua the Messiah, and the New Testament or the Testimony of Yeshua is about Yeshua. The following list of biblical books gives us a caricaturized sense of the Bible’s central and preeminent message.

- In Genesis, Yeshua is the eternal Torah-light of the world, the breath of life and the seed of the woman.

- In Exodus, he is the Passover lamb, the Torah-Word of Elohim, and the way to the Father in the tabernacle.

- In Leviticus, he is our atoning sacrifice and our high priest.

- In Numbers, he is the pillar of cloud by day and pillar of fire by night.

- In Deuteronomy, he is the prophet like unto Moses.

- In Joshua, he is the captain of our salvation who leads us into the kingdom of Elohim.

- In Judges, he is our judge and lawgiver.

- In Ruth, he is our kinsman redeemer.

- In 1 and 2 Samuel, he is our trusted prophet.

- In Kings and Chronicles, he is our reigning king.

- In Ezra, he is the builder of our temple, which houses the Spirit of Elohim.

- In Nehemiah, he is the rebuilder of the broken down walls of human life.

- In Esther, he is our Mordechai who saves us from those who would kill, steal and destroy us.

- In Job, he is our ever-living Redeemer.

- In Psalms, he is our shepherd to lead us in the ways of Torah-life.

- In Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, he is our wisdom.

- In Song of Solomon, he is our Loving Bridegroom.

- In Isaiah, he is the Suffering Servant who bears our sins, the Repairer of the Breach between the two houses of Israel, and the Prince of Peace.

- In Jeremiah, he is our Righteous Branch.

- In Lamentations, he is the weeping prophet.

- In Ezekiel, he is the one who rejoins the two sticks of Israel bringing them to worship Elohim together his temple.

- In Daniel, he is the fourth man in life’s fiery furnace and our Ancient of Day.

- In Hosea, he is the faithful husband forever married to the backslider.

- In Joel, he is the baptize of the Holy Spirit.

- In Amos, he is our burden bearer.

- In Obadiah, he is mighty to save.

- In Jonah, he is our great foreign missionary.

- In Micah, he is the messenger of beautiful feet.

- In Nahum, he is our strength and shield, and the avenger of Elohim’s elect.

- In Habakkuk, he is Elohim’s evangelist crying, “Revive thy works in the midsts of the years.”

- In Zephaniah, he is our Savior.

- In Haggai, he is the restorer of Elohim’s lost heritage.

- In Zechariah, he is a fountain opened up in the house of David for sin and uncleanliness.

- In Malachi, he is the Sun of Righteousness arising with healing in his wings.

- In Matthew, Yeshua the Messiah is the King of the Jews.

- In Mark, he is the servant.

- In Luke, he is the Son of Man, feeling what you feel.

- In John, he is the Son of Elohim.

- In Acts, he is the Savior of the world.

- In Romans, he is the righteousness of Elohim.

- In 1 Corinthians, he is the Rock, the Father of Israel.

- In 2 Corinthians, he is the triumphant one giving victory.

- In Galatians, he is your liberty. He set you free.

- In Ephesians, he is the head of his spiritual body.

- In Philippians, he is your joy.

- In Colossians, he is your completeness.

- In 1 and 2 Thessalonians, he is your hope.

- In 1 Timothy, he is your faith.

- In 2 Timothy, he is your stability.

- In Titus, he is truth.

- In Philemon, he is your benefactor.

- In Hebrews, he is your perfection.

- In James, he is the power behind your faith.

- In 1 Peter, he is your example.

- In 2 Peter, he is your purity.

- In 1 John, he is your life.

- In 2 John, he is your pattern.

- In 3 John, he is your motivation.

- In Jude, he is the foundation of your faith.

- In Revelation, he is the Righteous Judge of the world, the Avenger of the saints, your coming King, your First and Last, the Beginning and the End, the Keeper of creation, the Creator of all, the Architect of the universe and the Manager of all times. He always was, he always is and always will be. He’s unmoved, unchanged, undefeated, and never undone. He was bruised and brought healing. He was pierced to heal our pain. He was persecuted and brought freedom. He was dead and brought life. He is risen and brings power. He reigns and brings peace. The world can’t understand him, the armies can’t defeat him, the public schools can’t kick him out and the leaders can’t ignore him. Herod couldn’t kill him, the Pharisees couldn’t confuse him, the people couldn’t hold him, Nero couldn’t crush him, Hitler couldn’t silence him, the communists can’t destroy him, the atheists can’t explain him away, and the New Age can’t replace him. He is life, love, longevity and Lord. He is goodness, kindness, gentleness and Elohim. He is holy, righteous, mighty, powerful and pure. His ways are right, his word is eternal, his will is unchanging, and his eyes are on me. He is my Redeemer, he is my Savior, he is my Guide, he is my peace, he is my joy, he is my comfort, he is my Lord, and HE RULES MY LIFE!

Author Unknown, edited by Nathan Lawrence

Which Bible Translation Do I Use?

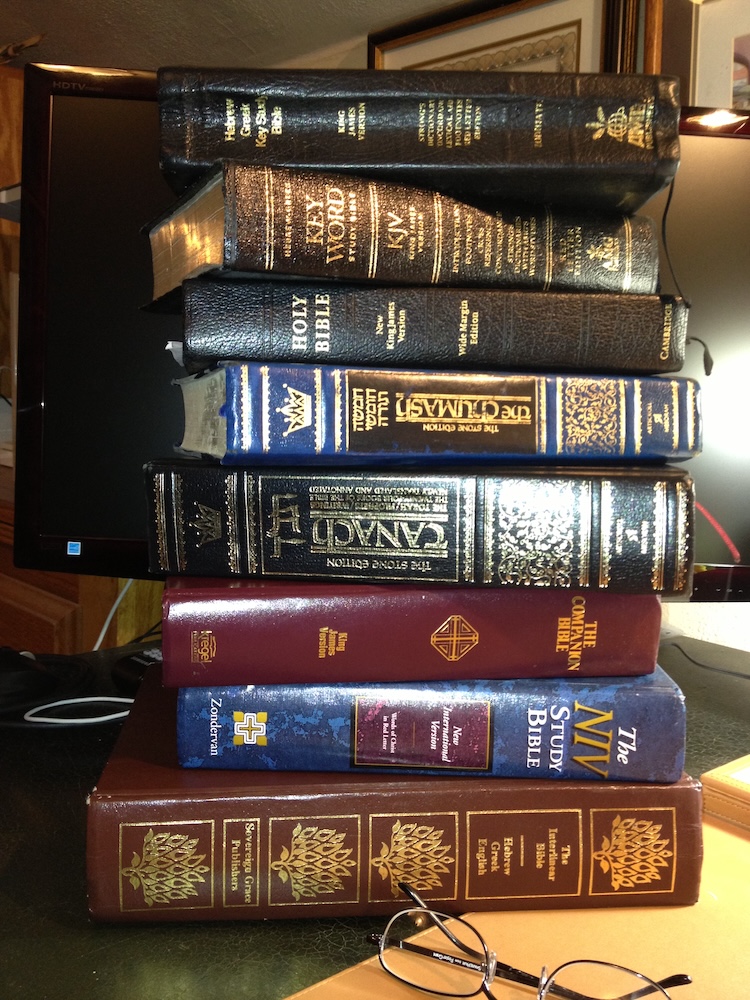

Continually, people ask me what Bible translation I personally use when preaching and when writing. I wish there were a definitive and conclusive answer to this question, but there is not. The short answer is this: all of the Bible translations and, at the same time, none of them. Let me explain what I mean.

The Word of Elohim is something that we must take very seriously. A godly and righteous man trembles before YHVH’s Word with a contrite heart (Isa 66:2). Admittedly, there are numerous Bibles being peddled by money-grubbing charlatans or self-proclaimed experts who have just enough knowledge of the original languages to be dangerous, but not enough to competently translate the Bible. This includes countless designer translations claiming to be true to the Hebraic roots of our faith by people who have little or no expertise in the Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek languages. These Bibles should come with a giant warning sign printed on the front cover, and should only be to read with great caution if at all! Many of these individuals are duping those who know less than they do when it comes to linguistics, and too many are preying on unsuspecting and naive people who are hungry for truth. They are proving the old adage that says “an ‘expert’ is simply someone who knows more than the next guy.” Most of these “translators” have little or no academic training or linguistic expertise in ancient biblical languages, yet this doesn’t stop them producing a constant stream of “new and improved” Bible translations. I actually have some academic background in foreign and biblical languages and have done translating work in both French and Koine Greek at the academic level, so I speak with some understanding on the subject. Yet, I am not an expert, and am not qualified to translate anything.

This disclaimer aside, there is not a single Bible translation on the market today that I can unreservedly recommend. Some of the more popular Hebraic roots or Messianic Bibles, for example, have likely been translated by individuals who have little or no linguistic training. How do we know this? This is because yet they (dishonestly) refuse to disclose publicly what their qualifications are for translating the Bible. I find this to be a huge red flag. If you have academic training in a foreign language, then state your bona fides , thus informing your readers of your qualifications. If you do not or cannot, then it is probably because you have none. Most likely, many self-proclaimed Bible translators of Hebraic version Bibles simply sat down with a copyright free English version (e.g., the KJV) and along with the help of a concordance and a few other lexical aids, made a translation, which they now peddle for big bucks. There is much more to understanding a language then simply viewing it through a concordance, lexicon or a few other lexical aids. There is complications of grammar, the nuances of syntax, and countless word plays and colloquial expressions that must be mastered, plus cultural and other contextual understanding and so much more that must be navigated in order to make a correct translations. To not take these issues into consideration is engaging in a dishonest and unrighteous endeavor and is toying with the Word of Elohim.

Now to the question at hand: which Bible version do I personally use? I still use the KJV and NKJV, since at least they were translated by competent linguists. Because after 55 year of studying the Bible and thus attaining a basic familiarity with many Greek and Hebrew words, I know where all the translation biases are, and I know the Hebrew and Greek words behind many of the English words in our Bibles. Thus, when reading the Bible (or when preaching and preaching) or quoting Scripture (when writing), I start with the base of the NKJV because minus the countless thees, thous, wouldests and shouldests my tongue is less likely to get tied. Then while reading or writing, I “clean” up the English. That is to say, I return the English names for deity back to their original Hebrew. For example, I insert Hebrew words for the names of deity (i.e., God becomes Elohim, LORD become Yehovah, Jesus becomes Yeshua, Christ becomes Messiah or Mashiach, Holy Spirit become Ruach HaKodesh, and so on). In cases where there are Hebrew or Greek words that have been translated into English using misleading words or biased translations, based on the lexical meanings of the words I make changes. For example, in Romans 10:4, I change “end” to “final aim, goal,”which is in accordance with the meaning of the Greek word telos as well Scriptural context. Another example would be Matthew 5:17 where fulfill (Gr. pleroo) means “to fill up, to make full, to complete, to fill to the top.” Additionally, in any place in both the Tanakh (Old Testament) or the Testimony of Yeshua (New Testament) where the word law occurs in referring to “the law of Moses”, I replace it with the Hebrew word Torah meaning “instructions, teachings and precepts [in righteousness of YHVH Elohim],” which is the primary meaning of torah.I could give many other examples, but hopefully the reader gets the point. The point is that I do not carelessly or haphazardly substitute words, but do so with a full understanding of the meanings of the words in the original languages, and how the biblical authors use them in the full context of the whole Bible. Again, we must tremble before YHVH (Isa 66:2) and his Word. I cringe at the thought of being labeled a false teacher, or bringing curses upon myself for adding or subtracting from the Word of Elohim (Rev 22:18–19; Deut 4:2; 12:32; Prov 30:6).

Understanding the Social World of the Bible

The Biblical Narrative—Story and Law Versus History. The Bible is more than history; it is a story. It doesn’t merely contain dry facts, which to the ancient Hebrews were meaningless. Rather, the biblical records facts-based stories that are interpreted that help the future generations to understand who they were. Therefore, the most common literature genres to be found in the Bible are story and law, not just historical facts. As Matthews and Benjamin point out, history is the genre of “what happened?” Story is the genre of “what does it mean?” As such, the biblical authors paint picture-stories using colorful and artistic language. The story teller is an artist, while the modern historian is a scientists (Social World of Ancient Israel, p. xix, by Matthews and Benjamin).

Religion Integrated Into Day-to-Day Life. In the world of the Bible, religion was a way of life pervading everything the ancients did. The Hebrews didn’t limit their religious experience to certain times, days or specific experiences as is often the case in the Western religious mindset. Religion was a thread that ran through the entire gamut of life every hour and day. Every season and year from regular household chores to sacred feast days were celebrated with religious ritual. Thus, religion inspired the culture as well as science and art. These were not only handed down from one generation to another, but were the ancient people’s profession of faith (ibid., pp. xix–xx).

Covenant Defined Relationships. Although family or blood relationships were important in the ancient world and were vital to survival, covenantal ties defined relationships even more than blood ties. Both blood and covenantal relationships were the glue that held households, clans, villages and tribes together in early Israel, but covenant more than kinship defined these relationships. Hebrew households were not only united by biology but by sociological experience, and these households shared legal commitments. The interaction between kinship can create confusion when the Bible uses familial terms like father, mother, son, nephew, uncle, brother and the like. In the Bible, these terms can be more legal than biological. In the ancient Near East, the practice of applying family titles to others outside of the biological family was common. For example, an apprentice often referred to his master craftsman mentor as father (ibid., pp. 8–9). Another unifying factor among the Hebrews was their common ancestry and the fact that they had passed from slavery to freedom. They also had in common the fact that they had left the world around them and had crossed through water whether the Red Sea or the Jordan River as a sort of rite of passage from one world to another.

The Role of the Mother in Ancient Israel. The mother was the sole manager of the household. Because ancient Israel was a subsistence economy, a household’s resources had to be managed carefully, and this was the woman’s responsibility. She directed the preservation and storage of food and allotted food rations to each family member to assure that everyone in the household was fed and the food lasted until the next harvest cycle. “In the world of ancient Israel, a man’s home was his wife’s castle, and she had the domestic authority which he did not (ibid., p. 25). The mother’s dominant role over the household including the children perhaps explains why Moses expected Zipporah to circumcise his two sons (Exod 4:25–26).

For the mother, childbearing and teaching children were synonymous roles. The Book of Proverbs shows the dual role of the mother (Prov 1:8; 6:20; 23:22–25; 31:1–9).

A mother’s intimate bond to her children not only lasted through pregnancy and infancy, but through the weaning process, which often didn’t occur until the child was four years of age. After teaching them how to walk, talk, dress themselves, she taught the child the domestic skills of gardening, cooking herding, weaving and making pottery (ibid., p. 28).

The Climate in the Land of Israel. Throughout the land of Israel (and neighboring lands), there are only two seasons: wet or winter (October through March) and dry or summer (April through September). Moist westerly winds blowing off the Mediterranean Sea produce the rain, while east winds blowing from the area of Arabia produce the warm and dry conditions.

Farming in the Land of Israel. The standard harvests of the hill country of Israel produced ten to fifteen times the grain that was needed for planting. This was the break even point for a farmer’s survival. A farmer could increase his yield and the success of his agricultural venture through capturing water through terracing hillsides, pooling resources with other farmers, having numerous children to help with farming activities, and by staggering sowing by planting a single crop in several stages over a period of time. In this way, farmers wouldn’t have to care for one large crop at the same time, and the same number of farmers could handle the same size crop one section at a time. Planting crops in stages provided insurance if the climate cycles happened to shift, so that crops would come ripe at different times (ibid., p. 39).

In the hill country of Israel, which is most of the land, it rained during only two seasons of the year. Rain occurred just before the planting season at the end of the summer in the fall. This rain was critical, since it loosened up the hardened, sun-baked soil, so that it could be plowed and planted. It also had to rain toward the end of the growing season to bring the crops to maturation (ibid., p. 43). These were the former (fall) and latter (spring) rains to which the Scripture make reference to in several places (Jer 5:24; Hos 6:3; Joel 2:23).

The standard clothing for a Hebrew peasant farmer was a tunic and loincloth. A cloak was added for colder weather and doubled as a sleeping blanket. These articles of clothing may have been the only ones a peasant possessed, since the Torah mandated that a cloak taken from a man in pledge by a creditor had to be returned to him by day’s end, so he would have a blanket to cover him at night (Exod 22:26; Deut 24:12–13, 17).

Some farmers not only raised crops, but had livestock as well not only to provide meat, milk, hides and wool, but as a insurance against a bad harvest. Often the youngest children were the herders, so as not to deprive the village of the heavy manual labor that older children could provide (see 1 Sam 16:11).

The Host and the Traveller. Since travelling in the ancient Near East was dangerous, the survival of the traveller depended on the hospitality of villagers. This reality gave rise to protocols pertaining to hospitality. Moreover, reciprocity demanded such protocols, so that when the roles of host and traveler were reversed the host now traveler would himself have accommodations. Therefore, the laws of reciprocity demanded that the head of a household treat travelers properly. This, in effect, was a village’s strategic foreign policy. However, a village couldn’t support a stranger for very long since feeding an extra mouth was expensive and strangers were a potential threat to a village’s status quo. Villages used hospitality to determine whether a stranger was friend or foe and whether they would be an asset or liability to the village economy. Therefore, by showing hospitality to a stranger for a short stay of several days at the most, this threat was neutralized, while at the same time the social convention demanding hospitality was upheld (ibid., p. 82). When a strangers accepted the invitation of a host, he was promoted to the status of a guest when the host washed his feet. Bathing signified a change in social status. Hosts would wash the stranger’s feet to signify they were now under the complete protection and care of the household (ibid., p. 85).

For the Hebrews there was an added impetus to show hospitality to traveling strangers. First, they had been strangers in a foreign land themselves, and YHVH didn’t want them to forget that. Second, the Israelites themselves were guests in the Promised Land (Deut 26:5–11; Ps 39:12). YHVH owned the land (Lev 25:23). As the divine landowner, it was YHVH who protected and fed his Israelite guests. The Israelites acknowledged this when they tithed the first fruits of their harvest to YHVH, and when the land was returned to its original owners every fifty years in the Jubilee Year. They were simply the land’s caretakers and were therefore to be conscientious stewards of it (ibid., p. 83).